Nearly every man who develops an idea works at it up to the point where it looks impossible, and then gets discouraged. That’s not the place to become discouraged.

[…]

The three great essentials to achieve anything worth while are, first, hard work; second, stick-to-itiveness; third, common sense.

— Thomas Edison

Carrie Nation, a radical feminist and member of the temperance movement (against alcohol before prohibition), went about busting up saloons in 1900 for a few months in protest of alcohol; she usually did this wielding a hatchet. A year later, Edison would capitalize on her popularity with the film Kansas Saloon Smashers. It’s only inevitable that films would cover topical subjects outside of boxing. Carrie Nation would later die in 1911, with her last words being, “I have done what I could.” In 1919, her dreams of national prohibition would be realized. One year later, women would be given the right to vote.

Generally, films tended to stay in 20-60 second lengths which people primarily viewed at locations the equivalent to a modern day arcade. Only instead of paying to play a game, you payed to look into a kinetoscope. Simple stuff, from seeing a train arrive at its destination, to a woman awakening from a giant clam that just opened up, to a brief comedic scuffle around a structure. It got monotonous. Less and less people went to these things. Film seemed like a dying fad. That was, until The Great Train Robbery arrived in 1903 in New York. A full-length feature film of 12 minutes, something largely unheard of back then. Viewed not by a traditional kinetoscope, but by a projector. Not only was its length astonishing, but so was its technique, introducing film concept of cross-cutting (cutting between two shots/scenes of action happening simultaneously). Motion picture popularity was re-ignited.

Something else significant to film also happened in 1903. Film distribution began to have some sort of order to them. In this year, two individuals named Harry J. Miles and Herbert Miles opened a film exchange in San Francisco. How it worked was film producers would sell their film to the film exchanges (ie distributors, aka the commission), and the exchange would lease the films to exhibitors (ie the equivalent of theaters). This more or less set up the first ever movie rental service. Move theaters, or buildings that would house kinetoscopes, rented films from the commission, which bought the films from the producers, who helped fund filmmakers so they could make their films. The film exchanges, operating as a rental service, supervised film circulation. Everybody turned a profit. A simple system, as it should be considering it is the one that started it all. Prior to this, turning a profit from film was more archaic, and didn’t suit theater owners all that well; which in turn prevented many people from seeing these movies. As a result of this new process, the film industry began to boom. Supply could not keep up with the demand.

Various religious unions, however, would rally against the films on ethical grounds, in spite of their demand. In 1906, The Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) condemned the influence of movies on the health, well-being and morals of impressionable youth. In 1911, the WCTU would erect a large gravestone honoring Carrie Nation for her prohibition efforts.

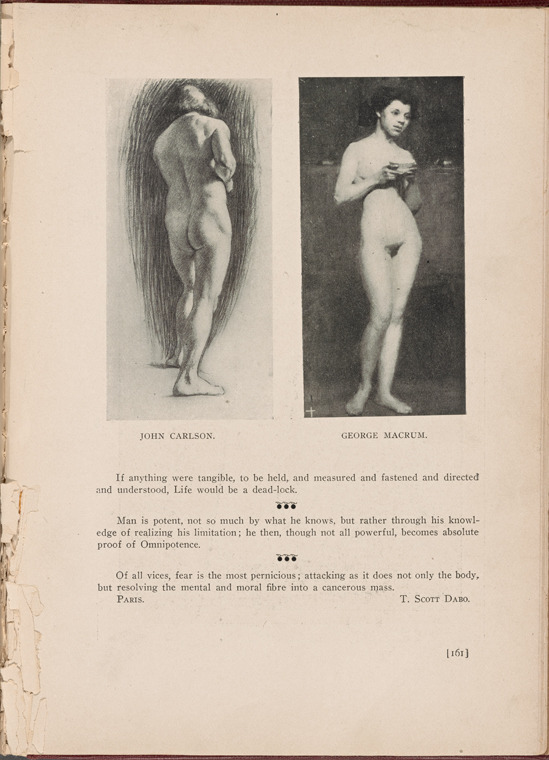

In the same year the WCTU publicly condemned films, postal inspector Anthony Comstock would raid the Art Student’s League of New York, in order to seize the publication The American Student of Art. Because of its depictions of nudity, which was deemed obscene, and thanks to The Comstock Act of 1873 (aka, “Act of the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use”), also deemed illegal. There was public backlash against this act of government censorship.

States continued their methods of censorship against motion pictures, now expanding beyond making it illegal to having boxing films, to outlawing films showing other acts deemed morally unfit for society. In 1907, Chicago, 2nd biggest film market at the time, the state made the first ever municipal censorship law, banning various films in their state. Films in Chicago couldn’t be legally exhibited unless given a permit by the local police chief. Despite this, nickelodeons had expanded to 3,000 theaters by this time. Censored or not, films were still being made, and their demand was as high as ever.

December 1908, a group of motion picture elites would organize the Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC), a film trust composed of The Edison Film Manufacturing Company, among other companies. The companies agreed to stop their competitive feuding over films, start co-operating, and thereby dominate the motion picture industry. They aimed to form a monopoly, where every film made had to be patented by them and their filming equipment. They succeeded. For the next few years, most money gained from the film industry went to the MPPC. In all fairness, they did this in-part to have a better defense against the local state police, which were seen as moral enforcers, who continually attacked the exhibitors by getting theaters shut down, and confiscating film, as a way to attack the producers. A monopoly was one method of fighting back against this. Regardless, a monopoly has its downsides. One of which was releasing similar uninspired drivel for audiences to see.

January 1909 was the deadline for all film companies to come under the wing of the MPPC. Those who didn’t became the first independent film companies, who were capable of making films outside the norm, by the MPPC’s standards anyway. By summer of 1909, the independent film market was in full-swing, utilizing illegal film equipment and illegal film stock (illegal because they were all patented by those in the MPPC, specifically Kodak, who was a part of the MPPC) to make their own films in an underground market. The MPPC did not ignore this. The MPPC formed the subsidiary known as the General Film Company (GFC). The GFC would crack down on the independent film market heavily, raiding their businesses, confiscating the cameras and film, sometimes destroying cameras and film.

Things escalated, with independents hiring their own goons for protection, who occasionally also found themselves in a film role. And why not? They were already on the payroll. Which made the supply of gangster films not only prevalent but topical in relation to the competitive nature of the film industry at the time. Things escalated even further with independents fighting over each other for film supplies and locations. They would even steal film reels from each other, and from the MPPC, showing each reel in one theater or another, leaving some sections of a motion picture incomplete at times in certain theaters. The chaos got bad enough to the point where theaters would burn down, sometimes by accident due to the highly flammable film, other times by arson. With the independents fighting each other, while also having to worry about the GFC and law enforcement, it was a losing battle for them. Many eventually went west to California, to Hollywood, to start producing films there away from the GFC goons (even though the MPPC was producing films there too).

In 1909, New York City (the location of the biggest film market at the time) established the New York Board of Motion Picture Censorship, who’s power and influence caused several other cities and states to follow suit with censoring films locally with their own censorship laws. This Motion Picture Censorship was largely Protestant influenced. The Protestant’s influence over the public’s calls for federal censorship would grow over the years.

Out of this monopolistic and religious oppression came an individual named William Fox. His interest in film began in 1904, in New York City, where the Board of Motion Picture Censorship would later be established. He began his career in films as a New York City film exhibitor/distributor. Knowing that he needed more monetary income from this business endeavor in order to be successful, he eventually opened up a theater in Brooklyn, New York, which could hold 600 seats. With the theater’s success, he began opening up more of them all around Manhattan, becoming more and more successful with his endeavor in exhibition. Eventually gaining favor and influence with the right politicians helped too, as his theater acquisitions grew larger in size over the years.

In 1912, he, along with the Republican administration who allegedly wanted to get back at the Democrats and their presidential nominee Woodrow Wilson for mentioning how he was going to fight against big business (which he stated the Republicans fully supported) by supporting the small businesses, brought legal action against the Motion Picture Trust for restraint of trade. He organized the Motion Pictures Association (MPA) to protect theater owners from Edison’s patent attorneys of the MPPC and GFC. By this time, the MPPC’s share of total film imports and production decreased from virtually 100% when the company was formed, to slightly more than 50% by 1912. With the MPA, William Fox launched and largely payed for the U.S. Department of Justice antitrust lawsuit that in 1915 formally dissolved the monopolistic MPPC and GFC, on the grounds that it violated the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. In addition, William Fox formed the Fox Film Corporation. The independents, or anyone for that matter, were free to make movies at last.

William Fox wouldn’t be the only one to form a film corporation, or the only one to take a stand against the monopoly. On the same year Fox filed a lawsuit against the Motion Picture Trust, Carl Laemmle, who also played a role in the battle against the film monopoly, founded the Universal Film Manufacturing Company in New York, which would eventually move to California and become Universal Studios. Also in 1912, Adolph Zukor (another figure about as significant as Willaim Fox when it came to altering the film production landscape), Daniel Frohman, and Charles Frohman would found the Famous Players Film Company, which would later on evolve into Paramount Pictures. In fact, Paramount Pictures became the first nationwide distributor of feature films, with its own coast-to-coast theater network. New film companies began forming left and right during these years, and would be able to enjoy their newfound freedom of film-making thanks to their efforts. By 1915, the term “movie mogul” came into being.

But they weren’t out of the woods yet. Not even close. Though the film monopoly had been broken up and producers no longer had to worry about patent laws, and goons from the GFC to bust up their places of business, there was still the issue of religious and women’s organizations calling for boycotts of various films in the industry. And the issue of local and state censorship remained.

The movies expanded into the middle classes without leaving their storefront audiences behind. In the realm of motion-picture attendance, the class distinction of American society began to slowly fade. The earlier hopes of the cultivated classes were at least partially attained when feature pictures conveyed their values to the lower orders. But the possibility of restoring cultural unity to American society through movies had slipped beyond the reach of the middle class. If anyone had the power to forge such a unity, it was the producers, many of them foreign-born Jewish immigrants, and their efforts would not be in the name of high culture but rather of mass entertainment.

Sources

Orbach, Barak Y. (2009) “Prizefighting and the Birth of Movie Censorship” Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities: Vol. 21, Issue 2, Article 3. Retrieved January 6, 2019 from DigitalCommons: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu&httpsredir=1&article=1348&context=yjlh

“A Brief History of Film Censorship” National Coalition Against Censorship. Retrieved January 6, 2019 from NCAC.org: https://ncac.org/resource/a-brief-history-of-film-censorship

Aberdeen, J. A. (2005) “The Edison Movie Monopoly: The Motion Picture Patents Company vs. the Independent Outlaws” Cobblestone Entertainment. Retrieved January 6, 2019 from Cobbles.com: http://www.cobbles.com/simpp_archive/edison_trust.htm

“20th Century Fox: American Motion Picture Studio.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved January 17, 2019 from Britannica.com: https://www.britannica.com/topic/20th-Century-Fox#ref206338

“William Fox.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. Retrieved January 17, 2019 from Encyclopedia.com: https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/william-fox

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1915/10/02/100179164.pdf

“A Timeline of the Pre-Code Hollywood Era” Pre-Code.com. http://pre-code.com/what-is-pre-code-hollywood/timeline-pre-code-hollywood-era/

Lewis, Jone Johnson. June 1, 2017. “Carrie Nation: Hatchet-Wielding Saloon Smasher” ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/carrie-nation-biography-3530547

Hanson, David J. “Carry Nation Biography (Carrie Nation, Carry A. Nation) Prohibitionist & Temperance Activist” Alcohol Problems and Solutions. https://www.alcoholproblemsandsolutions.org/carry-nation-biography-carrie-nation/

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Art & Architecture Collection, The New York Public Library. (1906-01). The American Student of Art. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/7c84e130-f31e-0131-618e-58d385a7b928

Amy Werbel, “The Crime of the Nude: Anthony Comstock, the Art Students League of New York, and the Origins of Modern American Obscenity,” Winterthur Portfolio 48, no. 4 (Winter 2014): 249-282. https://doi.org/10.1086/679370

Merrit, Greg. 2013. Room {1219} The Life of Fatty Arbuckle, The Mysterious Death of Virginia Rappe, And The Scandal That Changed Hollywood. Chicago Press Review Incorporated. Chicago, Illinois.

Sklar, Robert. 1994. Movie-Made America: A Cultural History of American Movies. Revised ed. Vintage Books. Random House Inc. New York, NY. Toronto, Canada.

Part 0, Part 1, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6

Edit (2-15-2019): Added in a bit of information as to a reason why the Edison monopoly was formed, how there was motivation to doing it outside of just simply getting rich and controlling the market.

Edit (3-30-2019): Added more details about how the Republican Administration assisted Fox (and others) who sued the MPPC and helped break up their monopoly. Also added an end-quote from Robert Sklar, from his book Movie-Made America.

[…] 0, Part 1, Part 3 Part 2, Part 4, Part […]

LikeLike

[…] 0, Part 1, Part 3 Part 2, Part 4, Part […]

LikeLike